- Код статьи

- S032150750005779-8-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032150750005779-8

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том / Выпуск №8

- Страницы

- 43-52

- Аннотация

For more than twenty years the Democratic Republic of Congo has been experiencing bloody conflicts which have resulted in millions of deaths. The intervention of international community had a limited success and violence continues to date. Despite abundance of academic literature related to the theme, there are very few papers which employ quantitative research to explain this violence. Furthermore, there has not been any research which illustrated conflicts in the country from the perspective of what is called infrastructural violence. The article aims to fill this gap and prove that infrastructural deficiencies are among the primary contributors to the violence in the DRC. The paper employs results of quantitative research and personal experiences of the author (three years as part of the UN mission in the country) to support its theoretical assumptions. The article might be very informative and helpful for the personnel of international organizations, the DRC Government and its donors. It might also be interesting for a broad circle of researchers from such areas as African, conflict and peace studies.

- Ключевые слова

- DRC, Congo, conflict, violence, infrastructure

- Дата публикации

- 10.08.2019

- Год выхода

- 2019

- Всего подписок

- 90

- Всего просмотров

- 2154

The Democratic Republic of Congo is seen by many as a vivid example of a failed state. Since its independence from Belgium in 1960, the country suffered conflicts on regional, national and local levels. The Second Congo War, which ended in 2003, resulted in more than 5 million deaths and became the bloodiest conflict since WWII [1; 13, p. 40]. In spite of the progress in restoration of peace since international pressure on belligerents, withdrawal of foreign troops and massive deployment of UN forces (MONUC/MONUSCO), the country continues to experience high rates of violence.

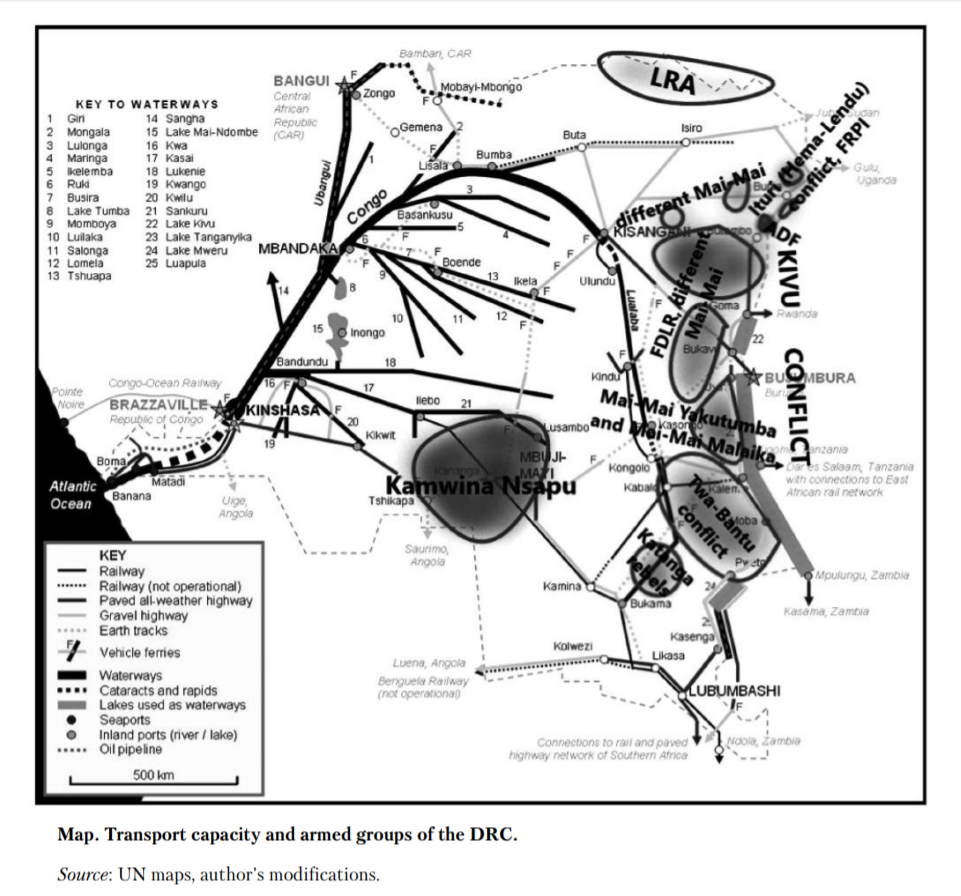

Since 2003, the country has been suffering a series of provincial scale conflicts. Starting in 2004, Nord-Kivu and Sud-Kivu provinces are subject to waves of fighting between different armed groups, fighting of them against the government as well as infighting. Ituri conflict, though in a lesser scale, continues its being since 2003. Katangese secessionist movements disbanded themselves only in 2016. Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) has been being active in Bas-Uele and Haute-Uele provinces over a decade. Starting in 2013, clashes between Twa pygmies and Bantu tribes have been ongoing mostly in Tanganyika province. They resulted in thousands of deaths [3] and more than 650 000 displaced [11]. Relatively new rebellion named Kamwina Nsapu erupted in Grand Kasai region in 2016. Despite absence of centralised organization and clear political program, the rebellion affected different provinces and caused more than 5000 deaths [19]. Meanwhile, it seems that these spots of violence generate and spread instability further as neighbouring to conflict zones territories become affected by violence as well.

As it is seen, the feature of the current state of conflict in the DRC in general is that there is no conflict in its traditional meaning. There is no strong enough active armed force or an alliance of forces with any political ambitions of country-scale to challenge the dominance of the current regime of power. None of cities or towns has been under control of an armed group in recent years. Nevertheless, activities of a multitude of outlaw groups have been causing casualties and other deplorable effects comparable to a conventional conflict. This asymmetric war is happening contrary to the efforts of international community aimed at stabilizing the situation. The country accommodates the biggest UN mission and force in the world. This raises the question whether the country’s government and international actors are addressing the root causes of the country’s conflicts or they are too engulfed with curing ‘disease symptoms’.

The existing academic literature explaining the conflicts in the country has mostly two flaws. Firstly, it almost does not employ quantitative research. This can be partially explained by absence of reliable statistics mostly in all spheres of the country. This, in turn, provokes the second problem - an obsession with conflict explanations which do not require a substantial statistical data to support their assumptions. The field is flooded with theories proposing different descriptive explanations of violence in the DRC or its parts: political disagreements [8]; autochthony, tribalism and regional nationalism [7; 12; 16]; unfair distribution of national income [5]; ‘conflict minerals’ [6] and corrupt power-sharing practices [15].

The current paper does not deny the mentioned factors as contributors to violence. Nonetheless, it argues that country’s conflicts these days are mostly caused by socio-economic reasons, rather than by those from other domains. The violence in the country collocates with degradation of infrastructure since the country got its independence in 1960. By late 2013, there were fewer than 31 000 km of operational roads (mostly located in Kinshasa, Bas- Congo, and southern Katanga regions), down from 145 000 km of roads in 1959 [14, p. 16]. As per 2019 the changes were insignificant.

As it is seen from the Map, the vast majority of violent occurrences are taking place in areas with poor road system and isolated from the biggest natural transport artery - Congo River and its tributaries.

This article argues that it is infrastructure deficiencies, including also those related to education and healthcare systems, which lead to violence, at least on basic, territorial level. Infrastructure deficiencies preserve backward economic model and society structure which, in turn, cause demographic pressures. These pressures in conditions of organised along bloodlines society and weak state performance create a breeding ground for existence of armed groups. Generated by armed groups violence, in turn, aggravates all segments of the mentioned problem chain and adds recursion to negative socio-economic processes.

The current paper starts with conceptual framework which defines mechanisms of infrastructure and violence interaction in the DRC. Theoretical propositions are also formulated in that part. After, there is presented research project aimed at gaining required statistics to support the theoretical propositions. The formed up by the research statistics about infrastructure and violence in the DRC is analyzed thereafter to support the propositions. Conclusion defines strong and weak parts of the paper and sets directions for further endeavours on the issue.

DEFINING MECHANISMS OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND VIOLENCE INTERACTION

Infrastructure and violence interact at territory (fr. territoire) level in three dimensions. Firstly, infrastructure deficiencies preserve subsistence agriculture model of society which, in turn, leads to demographic pressures and eventually related with them conflicts. Secondly, infrastructure deficiencies also cause growth in (illegal) artisanal mining which in realities of weak Congolese state creates a breeding ground for armed groups’ being. Thirdly, poor state of transport infrastructure prevents rapid deployment of security forces if a contingency arises.

Subsistence agriculture model which implies that ‘peasants… grow what they eat, build their own houses, and live without regularly making purchases in the marketplace’ [20, p. 8] is totally dominant in the DRC. It comprises all kinds of activities related, such as shifting cultivation, slash-and-burn farming, nomadic herding and intensive subsistence farming. Transition to more productive agricultural techniques is crippled by infrastructural problems, first of all, by transport infrastructure. The areas in proximity to waterways are in a relatively advantageous position due to poor state of roads or their absence is mostly compensated by transport capabilities of rivers and lakes.

Meanwhile, the landlocked areas suffer transport deficiencies in full. Inadequate state of roads makes transportation costs so high that farming oriented to selling agricultural products, especially for export, becomes unremunerative. Extremely poor state of roads in the DRC prevents exchange of goods and subsequently division of labour. It creates low basis for taxation and leads to a shrinkage of budgets in turn. The outcome is inability to provide satisfactory public services, first of all, building and rehabilitation of infrastructure. Underpayment of tax collectors, especially those who collect taxes on road checkpoints (these taxes are usually for funding maintenance of roads), motivates corruption among collectors and prevents budgets from incomes. Illegal taxation practices, especially on dreadful paths, only flame grievances to the state. Weakness of security forces and subsequent security problems, such as armed groups’ emergence, are the direct causes of underfunding and dire conditions the population lives. Also, a poor state of transport infrastructure cripples transportation of military personnel and relevant supplies, eventually preventing security forces to react quickly to outbursts of violence [4, p. 699].

Another problem caused by infrastructure deficiencies and subsequently by subsistence agriculture model is demographic pressures. Infrastructure deficiencies not only create low taxation basis and shrink budget incomes as was mentioned above. They also prevent farmers from accumulating necessary funds to rationalize and extend production. Mechanization of agriculture, construction of facilities for preservation and processing agricultural products become unaffordable as well as relevant educational opportunities. Inability to save a sum of money to buy a tractor or truck motivates a peasant to extend production by traditional methods - through increase in workforce. This trend is clearly visible as the country’s population roughly doubles every 25 years [17]. And the population growth rates intensified throughout the post-independence period despite wars, economic and infrastructural degradation [17]. Actually, the infrastructural degradation only increased the demand in labour force.

Demographic pressures, in turn, became a source of numerous problems of the Congolese society, such as land, communal and ethnic conflicts as well as educational and healthcare systems’ disbalances. Extreme share of young population or youth bulge became an issue by itself. The share of population in the Congo below the age of 15 has not been less than 45% and the number of children per woman less than 5,98 since 1950 [17].

According to Gunnar Heinsohn, when 30 to 40% of the males of a nation are from 15 to 29 years old, or in fighting age, youth bulge occurs [10, p. 16]. It follows periods with total fertility rates of 4-8 children or 2-4 sons per woman with 15-29-year delay. Thus, a father should leave 2-4 social positions instead of one to guarantee appropriate wellbeing of his sons - the goal difficult to achieve. Since society cannot produce respectable positions so quickly, more ‘angry young men’ appear and are biased to transform their anger into violence.

The above mentioned conditions perfectly match the situation in the DRC where the high number of unemployed youth offers armed groups an inexhaustible source for recruitment of combatants. The reservation wage of these young people is very low as they have no alternative income generating opportunities [13, p. 29].

Potentially, negative implications of demographic pressures can be successfully addressed by infrastructural development which may be both extensive and intensive. Simple rehabilitation of existing ramshackle roads may increase productivity of households and eventually contribute to reduction of demand in labour force. Thus, demographic pressures and violence may be decreased subsequently. Also, infrastructural projects create significant amount of workplaces that constrain unemployment and may have positive security implications.

Another extensive way of addressing transport infrastructure deficiencies, demographic pressures and eventually violence is building new roads. The current tribal/land conflicts in the country are for the territories which are accessed by existing infrastructure. Thus, simple increase of road network may help to accommodate more people. Congo’s vast spaces are mostly unexplored and the country’s population density is relatively low - only 34.8 per km2, though conflict regions mostly experience higher densities. Nevertheless, the experiences of neighbouring Uganda (157 per km2) and Rwanda (445 per km2) showed that demographic pressures can be addressed successfully by extended transport infrastructure creation.

Finally, infrastructure deficiencies and preserved by them backward agriculture model provoke rise in artisanal mining which contributes to violence in turn. The backbone of this link is transportation costs. As it was mentioned above, poor state of transport network increases transportation costs drastically. This makes profits of peasants who grow their crops for sale miserable. Thus, in areas endowed with easily extractable and easily transportable minerals (gold, diamonds, coltan and cassiterite), the population looks for gaining better profits through involvement in mining activities. Extraction of these resources does not require significant investments in mining sites construction. Transportation costs are also low while profits are significant.

The problem is that the combination of a weak state and abundance in natural resources creates opportunities for different agents (internal and external) to take advantage of the power vacuum to exploit natural resources [13, p. 22]. Also, such mining sites quickly become objectives of parties and means of their financing. Different ethnic groups and associated with them militias start to claim them and use force to support such claims, adding ethnical dimension to conflicts. An intervention of governmental forces is often considered by other belligerents as meddling of outsiders into their local affairs and fighting continues already against the invaders.

As roads and other infrastructure make up an important part of public expenditure, their length and state may serve also as an indicator of importance attached by state government to a particular region [4, p. 699]. A poorly developed transportation network in one area in comparison with other ones is ‘a possible sign of political marginalization and strained relations with the capital region’ [4, p. 698]. These infrastructural deficiencies and disbalances contribute both to anti- state grievances and to a general feeling of abandonment which can encourage violent self-help strategies. These grievances are even more aggravated by historical ‘resource nationalism’ in some regions (for example in Katanga and Sud- Kasai). Thus, at the country level, the lack of infrastructure became not just an economic problem, but a political challenge endangering the unity of the DRC [9, p. 57].

To sum up, the central argument of the paper is that infrastructural deficiencies play significant (if not the central) role in DRC violence. Three theoretical propositions which require to be supported statistically are listed hereunder:

1. Infrastructural deficiencies correlate with violence.

2. Infrastructural deficiencies correlate with demographic pressures.

3. Advanced infrastructure prevents violence by compensation of shortage of land.

RESEARCH DESIGN, DATA ACQUISITION, DATA PROCESSING AND STATISTICS

Overall research design

The main idea of the research was to establish possible correlation between level of violence and level of development/degradation of infrastructure in DRC conflict zones. To achieve this aim there was collected data about violence in the country, established territories (administrative territorial units which form up provinces) affected, and the data was structured the way that there was a standard dossier for each territory. The dossier contained a list of violent events with counted results (numbers of killed, wounded, abducted, internally displaced etc.).

The next step was collection of data about infrastructure (lengths and conditions of roads, railways, waterways, numbers of schools and hospitals etc.) on violence affected territories. Additionally, there was collected the same kind of data regarding infrastructure on some neighbouring peaceful territories, so there was formed the control group. The sets of data about violence and infrastructure were scored applying the same standards after. Thus, it became possible to establish shares of each territory in overall violence and in overall infrastructure. By juxtaposing shares of violence, infrastructure, population and land it became possible to establish correlations between them.

The research embraced time period of 40 months - from January 2015 to April 2018. Firstly, the logic of the time choice was that the country did not experience any significant outside meddling in its affairs within the period, so the violence was almost intrastate. Secondly, it was manageable to acquire data regarding level of violence and state of infrastructure in different territories for the period.

Problems in acquisition of violence data

Author’s personal experience of being part of the MONUSCO showed that the mission lacked statistics regarding violence outbreaks in a format required for the research. Other UN agencies’ reports, such as those of the UNHCR and the OCHA, in spite of certain usefulness also generally did not qualify the criteria.

Another primary source of information regarding violence could have been the Armed Forces of the DRC or FARDC, but it appeared that the governmental body also did not have required statistics. Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), an international peace and conflict research platform which generates statistics about fatalities in conflicts, was also rejected as it did not count wounded, raped, abducted, internally displaced people and other violent occurrences.

After all the mentioned above potential sources of statistics were screened and rejected, there was taken decision to use Radio Okapi, a MONUSCO sponsored Congolese news agency, as a primary source of data for creation of the database of violent events. The first reason why Radio Okapi was chosen was that it was possible to compare its reports with actual situation on the ground. Secondly, the news agency was a relatively independent, presumably non-biased source of information. Mostly, it was due to the fact that Radio Okapi was sponsored and protected by the UN. Thirdly, the source was broadly recognized even outside the country.

The process of creation of the violence database required for the research comprised the following. Firstly, there were read and processed all news published on Radio Okapi website which pertained to violence in the country for the chosen period. Each violent occurrence was reflected by an entry in the database with the following parameters: date, territory, belligerents and outcome. The second step was to score the outcome of each violent event applying the same standards. Summing all the scores of the database and counting all the scores for a particular territory it became possible to establish the share of overall violence each territory had. The third step was creation of derivative statistics required for the research.

Problems in acquisition of infrastructure data

The only source of available statistics or data for compiling statistics about the state of infrastructure in territories was the website of CAID (fr. Cellule d’Analyses des Indicateurs de Developpement), a governmental statistical organ. Despite the option of downloading required statistics, the reality was that the statistics presented on the website was structured with significant errors and was considered not useful for the research.

Nevertheless, the website contained required non-structured data about territories, such as their population and territory (km2), number of primary and secondary schools, universities, vocational facilities, health centres and hospitals. The structured data about transport infrastructure (roads, railways and waterways’ infrastructure) was unreadable, but the website contained maps of territories. There was conducted manual metering on these maps to get necessary statistics about transport infrastructure: length and state of roads and railways, length of waterways etc.

For the research there were selected maps of 55 territories, including 45 territories affected by violence. The remaining 10 suffered significantly lesser violence or were in peace, but had borders with territories in conflict. These 10 maps were selected randomly, but each from a different province. Thus, they filled the control group.

There was collected data about transport infrastructure, educational infrastructure and healthcare infrastructure for each territory. The collected data about infrastructures was structured in a table and scored with same standards. Each territory received a number of infrastructure points for its infrastructures. Summing all the scores of database and counting all the scores for a particular territory there was established a share of overall infrastructure each territory had.

Statistics usage

After the required statistics about violence, infrastructure and other parameters was extracted and distilled for each territory, it became possible to mould this data into different sets to establish correlations between them. It allowed defining the role infrastructure played in violence outbreaks for each territory. Secondly, it created space for engagement with academic literature about DRC conflicts and peace research in general.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

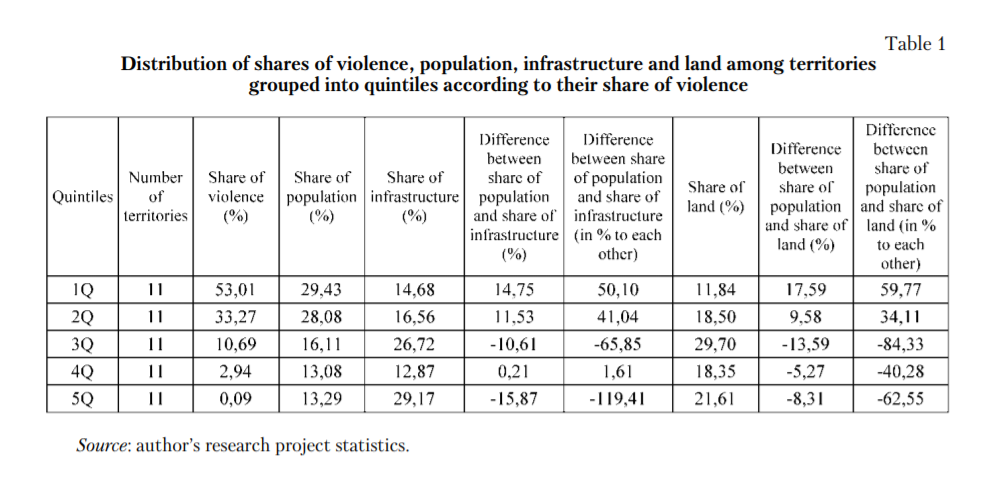

The data presented in Table 1 reflects distribution of shares of violence, population, infrastructure and land among territories grouped into quintiles according their share of violence (1Q - the most violent territories and 5Q - the least ones).

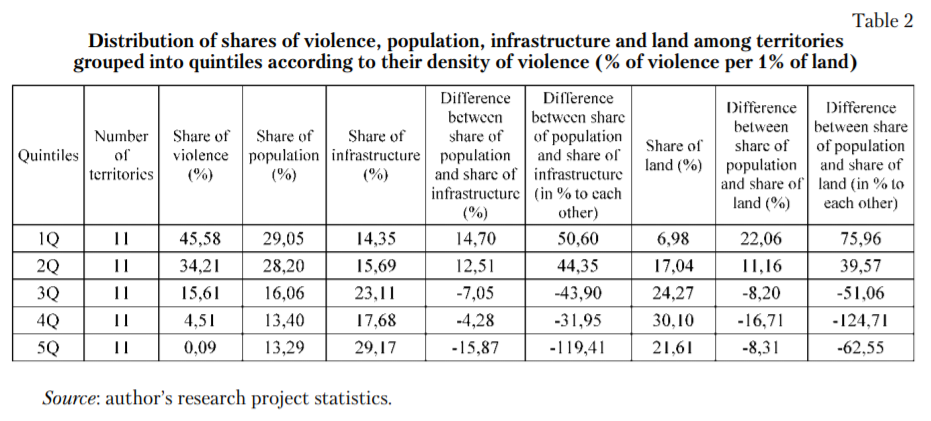

As it is seen from Table 1, there is no strict correlation between share of violence and difference between share of population and share of infrastructure. Neither there is a strict correlation between share of violence and difference between share of population and share of land. This can be explained by presence of factors different from infrastructure and land deficiencies in formation of violence-prone environment. Nonetheless, there is a general correlation which is also better seen if the territories are grouped into quintiles according their density of violence (% of violence per 1% of land) - Table 2.

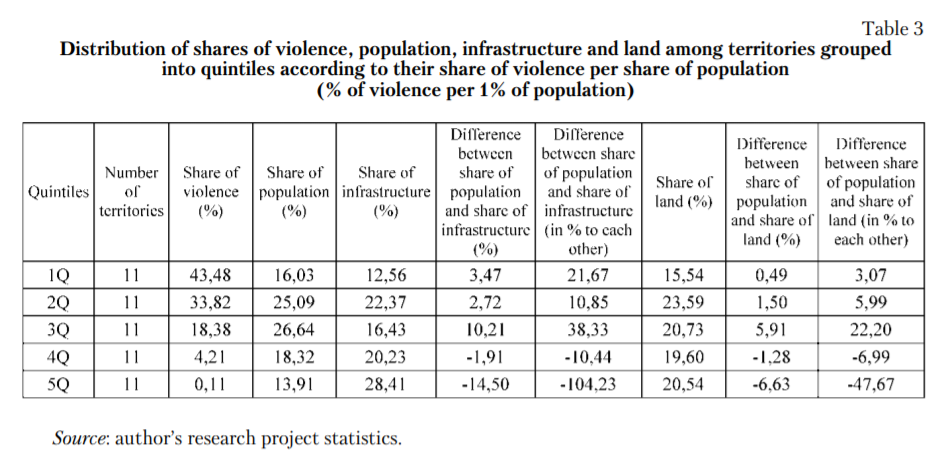

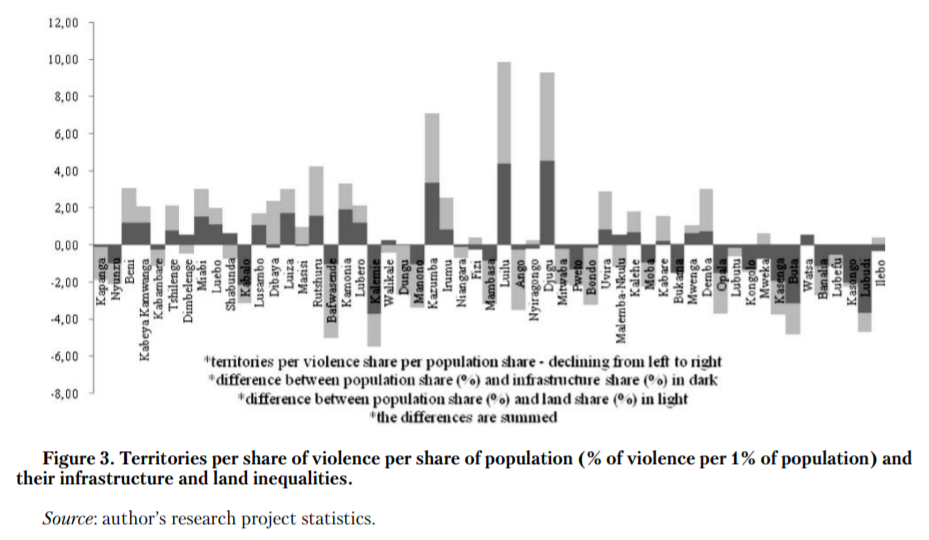

Correlations are worse if the territories are grouped into quintiles according their share of violence per share of population (% of violence per 1% of population) - Table 3. Possible interference of factors different from infrastructure deficiencies and demographic pressures is seen: it is 3Q which has the worst disproportions. The general dependencies though are still vivid if 1Q and 2Q are compared with 4Q and 5Q.

The general correlations between share of violence and difference between share of population and share of infrastructure as well as between share of violence and difference between share of population and share of land are present. Especially, it is vivid if 1Q and 5Q are compared in all tables. It is also seen in 5Qs in all tables that land size plays a lesser role than availability of advanced infrastructure in violence prevention.

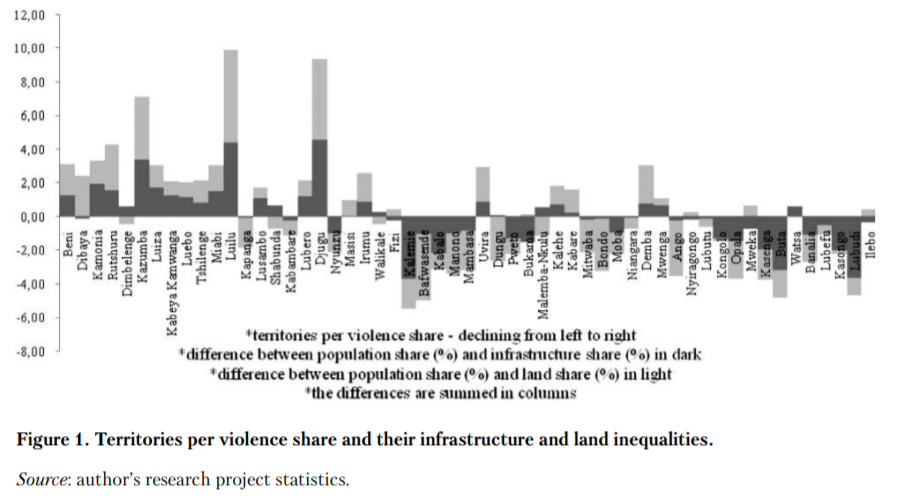

Figure 1 visualizes infrastructure and land inequalities of territories ranged according their share of violence. As it is seen, generally, the territories with infrastructure and land deficiencies are prone to conflicts.

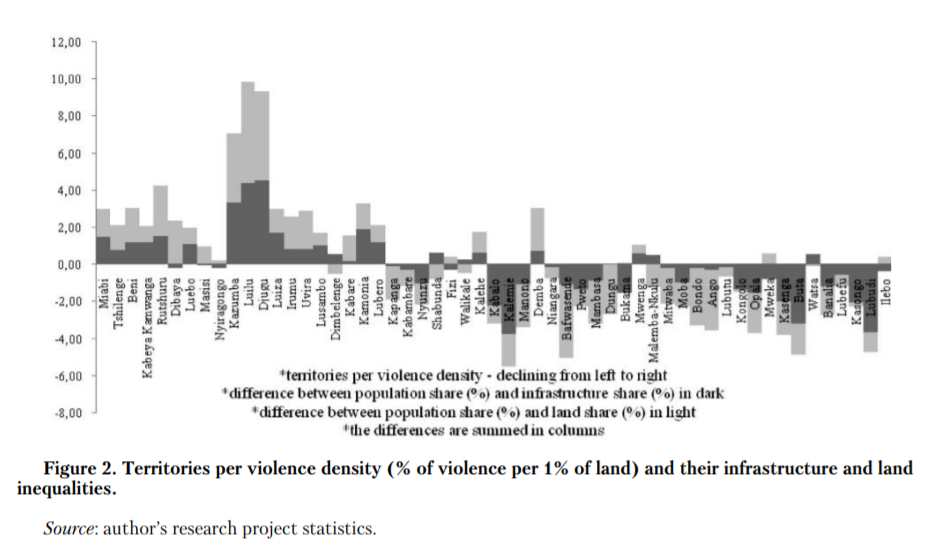

A stronger correlation is seen in Figure 2 where the territories were ranged according their density of violence (% of violence per 1% of land).

A weak correlation is seen in Figure 3 where the territories were ranged according their share of violence per share of population (% of violence per 1% of population).

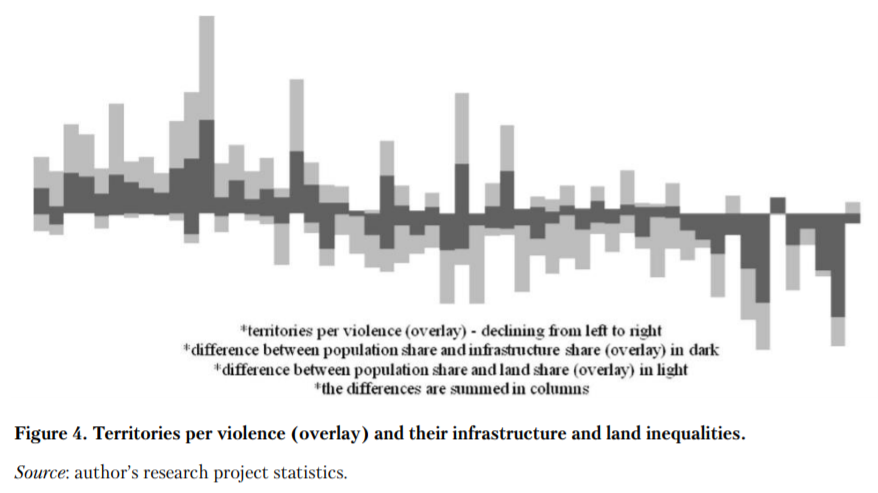

Figure 4 which is the overlay of Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 is the concentrated graphical output of the research. It represents the data received from the review of approximately 1000 news reports, measurements of 55 maps of DRC territories and screening dozens of web-pages.

As it is seen in Figure 4, there is a general correlation between violence and infrastructure deficiencies. The most violent territories (on the left) generally have positive differences between population share and infrastructure share while the opposite is seen on the right where the least violent territories are. Thus, the results contribute to the first theoretical proposition of the paper which says that infrastructural deficiencies correlate with violence in the DRC.

A weaker correlation between violence and difference between population share and land share is also seen in Figure 4. Nevertheless, the diagram supports the second theoretical proposition of the paper which says that infrastructural deficiencies correlate with demographic pressures. It is seen on the left that land deficiencies correlate with extreme violence while on the right it is seen that moderate availability of land is compensated by extended infrastructure. This contributes to the third theoretical proposition of the paper which says that advanced infrastructure prevents violence by compensating shortage of land.

Though the presence of factors different from infrastructure and land deficiencies is seen, the general correlations confirm all three theoretical propositions and the general argument of the article which is that infrastructural deficiencies play significant (if not the central) role in DRC violence.

CONCLUSION

The paper was an attempt to explain conflicts in Congo statistically and establish the role of infrastructure in formation of violence-prone environment. To achieve this goal there was conducted extensive research project. The result of the project was the relevant statistical information which supported the theoretical propositions had been made. It was proved that infrastructural deficiencies play important role in violence in the DRC. In fact, these deficiencies might be the cornerstone of the current state of conflict and addressing them may be a remedy for the country.

The strong part of the article, besides employment of quantitative methods, is that it scrutinised the conflict in the DRC from infrastructural perspective. This fact makes the paper a pioneer in a relatively new area of conflict studies dedicated to what is called infrastructural violence. Meanwhile, the statistics used in the article is mostly based on data collected from a news agency (though a respectable one) and a governmental body which is presumably poorly financed. The data-processing techniques mostly relied on common sense rather than on standard methods (whether there are any applicable to the case). Thus, discovering new, more trustworthy sources of data and application of specialized techniques for data-processing may correct the statistics. This in turn can help to indicate better the place of infrastructure in Congo conflicts. Broader timeframes can be grasped to establish better correlations.

Библиография

- 1. Bavier J. Congo war-driven crisis kills 45,000 a month: study // Reuters, 22.1.2007 - https://www.reuters.com/ article/us-congo-democratic-death/congo-war-driven-crisis-kills-45000-a-month-study-idUSL2280201220080122 (accessed 21.02.2019)

- 2. Cellule d’Analyses des Indicateurs de Developpement, the Government of the DRС - https://www.caid.cd (accessed 03.03.2019)

- 3. Clowes W. Displaced Congolese civilians sent back to a widening war // Irinnews, 11.07.2017 - http://www.irinnews.org/feature/2017/07/11/displaced-congolese-civilians-sent-back-widening-war (accessed 11.03.2019)

- 4. Detges A. Local conditions of drought-related violence in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of road and water infrastructures // Journal of Peace Research, 2016, 53:5, pp. 696-710.

- 5. Englebert P., Mungongo E.K. Misguided and Misdiagnosed: The Failure of Decentralization Reforms in the DR Congo // African Studies Review, 2016, 59:1, pp. 5-32.

- 6. Geenen S., Claessens K. Disputed access to the gold sites in Luhwindja, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo // Journal of Modern African Studies, 2013, 51:1, pp. 85-108.

- 7. Gobbers E. Ethnic associations in Katanga province, the Democratic Republic of Congo: multi-tier system, shifting identities and the relativity of autochthony // Journal of Modern African Studies 2016, 54:2, pp. 211-236.

- 8. Hale A.Z. In Search of Peace: an Autopsy of the Political Dimensions of Violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo // University of Florida, 2009.

- 9. Herderschee J., Kaiser K.-A., Mukoko D. Resilience of an African Giant: Boosting Growth and Development in the Democratic Republic of Congo // The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2012.

- 10. Heinsohn G., Weltmacht S: Terror im Aufstieg und Fall der Nationen // Zurich: Orell Fussli, 2003.

- 11. ICRC - Stricken by communal violence and malnutrition in Tanganyika, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 3.1.2018 - https://www.icrc.org/en/document/democratic-republic-congo-communal-violence-malnutrition-tanganyika (accessed 13.03.2019)

- 12. Jackson S. Sons of Which Soil? The Language and Politics of Autochthony in Eastern D.R. Congo // African Studies Review, 2006, 49:2, pp. 95-123.

- 13. Ndikumana L., Kisangani E., Kalonda-Kanyama I. Conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Causes, impact and implications for the Great Lakes region // United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2015, pp. 1-112.

- 14. RDC - Rapport Annuel d’Activites // Office des Routes, Kinshasa: Gombe, 2012.

- 15. Simons C. Power-sharing in Africa’s war zones: how important is the local level? // Journal of Modern African Studies, 2013, 51:4, pp. 681-706.

- 16. Tull D.M. Troubled state-building in the DR Congo: the challenge from the margins // Journal of Modern African Studies, 2010, 48:4, pp. 643-661.

- 17. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision - https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/DataQuery/ (accessed 03.01.2019)

- 18. Uppsala Conflict Data Program: Methodology - http://pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/methodology/ (accessed 11.02.2019)

- 19. VOA - UN Investigator: Atrocities in DRC Fall Short of Genocide, 3.8.2018 - https://www.voanews.com/a/uninvestigator-atrocities-in-drc-fall-short-of-genocide/4512694.html (accessed 10.02.2019)

- 20. Waters T. The Persistence of Subsistence Agriculture: life beneath the level of the marketplace // Lexington Books, 2007.