- Код статьи

- S032150750009876-5-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032150750009876-5

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том / Выпуск №6

- Страницы

- 37-42

- Аннотация

In order to join the European Union, candidate countries have to meet a specific set of conditions (the Copenhagen criteria), which include maintaining stable institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities. Incentivising the countries wanting to join the EU to strengthen democratic institutions, EU membership conditionality - tying the possibility of membership to compliance with membership conditions - is considered to be an effective tool for promoting democracy and the rule of law. However, the effectiveness of conditionality was recently questioned by an authoritarian turn in Turkey and democratic backsliding in other candidate countries.

The question that arises from recent developments is whether EU membership conditionality, based on rewards rather than sanctions (“positive” conditionality), is equipped to deal with democratic backsliding in candidate countries. This article closely examines the EU’s choice of responses addressing the problem of democratic deterioration in Turkey, the country with the most drastic dismantling of democratic institutions amongst the candidate countries, and assesses the scope and limits of the tools the EU employed to redress severe democratic backsliding.

The article concludes that positive conditionality by itself is limitedly equipped to effectively counteract the consolidation of authoritarianism. For Turkey, the situation was also aggravated by the lack of expertise on the part of the EU, which previously had no experience in dealing with democratic backsliding in candidate countries. Additionally, there were instances of conditionality being applied inconsistently, compromising its credibility. What also affected the application of conditionality is the leverage Turkey gained in EU-Turkey relations due to the EU’s need to enlist the country’s support in curbing the flow of Syrian refugees to Europe. Combined, the problems resulted in the ineffectiveness of measures taken to counteract democratic deterioration in Turkey.

- Ключевые слова

- EU conditionality, EU enlargement, democratic backsliding, Turkey

- Дата публикации

- 27.06.2020

- Год выхода

- 2020

- Всего подписок

- 35

- Всего просмотров

- 2262

EU membership conditionality is considered to be one of the most effective tools at the EU’s disposal for promoting democracy, stability and rule of law in its neighborhood.

The success of conditionality was exemplified by the 2004 enlargement round, when 10 Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs) successfully joined the EU. The EU further enlarged in 2007, when Bulgaria and Romania joined the Union, and in 2013, when the EU welcomed Croatia. After that, the EU was planning to expand even further, to include Turkey and the whole of the Western Balkans. However, what once seemed to be a promising enterprise given the successful track record of EU conditionality is now marred by troubling developments.

The most drastic case of backsliding in the immediate European periphery is Turkey, which moved in the Freedom House rating from a stable partly free (3.0) in 2012 to an alarming not free (5.5) in 20181. A similar trend, though not (yet) of the same proportion, is evident across the Western Balkans [1; 2].

Now that the authoritarian trend in EU candidates is manifest to the extent that it can no longer be ignored, a number of questions arise. What can the EU do to counteract backsliding? What has it been doing? Has it been enough?

The question that the EU is not likely to escape is whether the Union had not been too lenient on smaller, but already noticeable instances of disrespect towards democracy and human rights for too long [3]. Another question, and perhaps an even deeper one, is whether the EU could do any differently, with the tools available.

EU accession conditionality heavily relies upon the idea of positive incentives in the form of prospective membership. The prospect of membership provided enough incentives for the CEECs, with carrots (rewards) rather than sticks (punishments) proving to be sufficient to incentivize pro-democratic change. However, one cannot expect carrots to always be juicy enough [4]. With no sticks at hand and the 2004 enlargement round being largely successful, the EU had little experience and practical tools to deal with severe breaches against the European principles when it took upon itself much trickier candidates.

Looking closely at Turkey – the “trickiest’ candidate with the longest history of the accession process and the most dramatic backsliding, this article analyses what the EU has been doing to counteract democratic backsliding and deterioration in human rights.

The analysis concludes that the failure of the EU to counteract the worrying trends may be linked to the general lack of instruments against backsliding within the type of conditionality employed by the EU for the accession process (positive conditionality), inconsistent application of conditionality, and mismatched reactions.

EU CONDITIONALITY: THE “POSITIVE” SIDE

EU membership conditionality is a vibrant example of positive conditionality. Countries are offered benefits in exchange for their compliance with accession conditions. Target countries decide by themselves whether the benefits outweigh the costs of compliance and face no additional sanctions if they are not interested in EU accession as a result of that calculation.

One can compare EU conditionality with a strategy of “reinforcement by reward” [5]. Guided by this strategy, the EU reacts to compliance by granting rewards, and to non-compliance by withholding them. That is in contrast to reinforcement by punishment, where non-compliance leads to extra costs (“punishment”) [5, p. 497].

Although with time the accession framework came to include more safeguard clauses [6], the general approach remains positive in the sense that the heaviest possible penalty (suspension of accession negotiations) is withholding the rewards rather than inducing extra costs.

The obvious advantage of this approach is that it allows the EU to exercise considerable transformative power in its neighborhood without unlawfully intervening in the countries’ domestic politics. However, positive conditionality is not without its weaknesses: with EU membership constituting the highest reward possible, there is little that the EU can do if the proposed benefits prove to be insufficient to induce democratic change [5, p. 515]. The only sanctioning power at the EU’s hands – withholding the reward – can only pose a threat to the candidate country when it still considers the reward beneficial.

EU CONDITIONALITY IN TURKEY BEFORE THE REFUGEE CRISIS

The earlier period of AKP rule (Adalet ve Kalkýnma Partisi – Justice and Development Party) is conventionally described in the literature as “the golden age” of Turkey’s democratisation efforts [7].

In the 2002-2005 period Turkey introduced a multitude of democratic reforms and was finally rewarded with opening membership negotiations. But the golden age failed to last. The first obstacle in the accession process came in 2005 when Turkey refused to implement the Additional Protocol with regards to the Republic of Cyprus. That first visible instance of non-compliance was followed by a resolute step from the EU: eight negotiation chapters were closed until Turkey would fully implement the Additional Protocol [8].

Within the framework of positive conditionality the move can be regarded as withholding the reward until compliance is ensured. Additional chapters were blocked by France and Cyprus in 2007 and 2009, respectively. That led to a stalemate in accession negotiations and a slowdown in pro-EU reforms.

Researchers differ in their judgments as to the exact moment when the slowdown of the reforms gave way to their reversal.

Some argue that the illiberal turn could be noticed as early as 2010 [9]. First, the judicial reforms introduced as a part of a harmonization package raised concerns as to whether the reforms were directed at increasing judicial independence, as intended by the EU, or just the contrary – bringing the judiciary under the control of the executive [9, p. 136]. Secondly, the way Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases were conducted attracted considerable criticism both inside and outside Turkey. In its reaction in a yearly Progress Report, the EU took notice of some of the procedures falling short of legal and democratic standards, such as the length of pre-trial detention and equal judicial guarantees for all suspects [10].

At the same time, the general mood of the report remained positive, with the EU encouraging Turkey to stick to the standards rather than criticizing Turkey for falling short of the standards so far. That said, provided that the target country is interested in acquiring the benefits, actively monitoring compliance and openly "exposing" misfits between the criteria and the country's attempts at their implementation is a valid reaction that can have a positive influence on the level of compliance.

Including such observations in the report can strengthen conditionality, sending the target country a signal that the reward will not be obtained unless the country genuinely complies with the criteria. However, in practice the initial “exposing” approach of the EU failed to generate any substantial change of heart by the Turkish government, which would become even more evident in the years to follow.

If 2010 is viewed only by some of the researchers as the turning point of breaking away from a prodemocratic course, 2013 is almost universally agreed to be the year when democratic deterioration became painfully evident.

In May-June 2013 a violent police crackdown on the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul revealed the government’s intolerance towards any kind of opposition. The EU’s reaction to the developments in Turkey was cautious. In its annual Progress Report, the EU did make notice of the police’s extensive use of physical force (“exposing”) and – to some extent – condemned it [11].

However, instead of criticizing the government’s decision to crush down on the protesters, the EU chose to frame the extensive use of police force as a series of unrelated police offences by individual police officers, effectively shifting the blame to the effectors of the orders rather than their source. Moreover, the EU praised the Turkish Ministry of the Interior for taking a “a first positive step by issuing circulars to regulate the conduct by police officers during demonstrations” and conducting administrative investigations into individual law enforcement officers [11, pp. 2-6].

Overall, the tone of the 2013 Progress Report remained positive, with the EU even praising Turkey for “good progress ... made in terms of establishing Turkey’s human rights mechanisms and institutions” [11, p. 13], despite numerous allegations of breaches against human rights during the protest crackdown. That said, the “exposing” of the extensive use of force was still officially performed, signalling to the target country that an incidence of non-compliance was not unnoticed.

When analyzing the EU’s hesitancy to openly condemn the developments in Turkey, it is important to understand that the Gezi protests happened shortly after the launch of the EU-Turkey Positive Agenda, a framework designed by the EU to give a boost to Turkey’s accession process after a few years of a de facto stalemate.

Unable to reinforce compliance “by reward” due to Turkey’s lack of meaningful progress in accession negotiations, the EU endeavored to boost the effectiveness of conditionality by “cheerleading” Turkey into compliance, which included praising Turkey for whatever progress has been made and avoiding harsh criticism when progress was missing.

Another development unmasking the growing rule of law and democratic deficits was the government’s fight against the Gulen movement, which escalated to large-scale purges following the December 2013 corruption investigation against major governmental officials. Erdogan faced criticism from EU leaders already in January 2014 (“condemning”), with European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso publicly announcing the EU’s concerns over police and judicial purges and reminding Turkey that separation of powers and respect for rule of law were essential conditions of EU membership [12].

This reaction has a few notable features. First, the EU reinforced the reaction of “exposing” with a reiteration of conditions – an act of reminding the target country that the reward will only be achieved if the membership conditions are met. It is also worth noticing that the reaction came quite quickly, with the EU deciding not to wait for the next Progress Report to indicate its dissatisfaction.

Additionally, the EU chose to communicate its message publicly, which is also a way to “upgrade” the reaction and exert additional (social) pressure on the target country.

This newly taken approach of public criticism from EU leaders manifested itself again in February 2014, when President of the European Parliament Martin Schulz publicly called new Turkish legislation establishing tight control over the Internet “a step back in an already suffocating environment for media freedom” [13]. In the Progress Report, the EU repeated its concerns regarding the separation of powers and fundamental freedoms[14]. No material sanctions followed.

Overall, when the first episodes of democratic erosion became evident, the EU not only stayed away from “punishments”, but also refrained from some of the tools it had even within the positive conditionality approach, such as suspension of negotiations or putting financial assistance on hold.

In other words, the EU did not exhaust the full range of options. Another important finding is that the scope of the tools to address democratic backsliding, although limited, provided an opportunity to “upgrade” the response, starting with simple monitoring and “exposing”, scaling up to “reiteration”, “condemnation” and “pressure” and potentially suspending the accession negotiations. Moreover, one could adapt the response to the severity of noncompliance by fine-tuning the tone, frequency, level of publicity and the number of channels through which the reactions are transmitted.

EU CONDITIONALITY AND THE REFUGEE CRISIS

The year of 2015 brought an exogenous shock of the refugee crisis and greatly affected EU-Turkey relations, undermining the asymmetry on which conditionality relies to be effective. The asymmetry implies that the candidate country is to gain more from joining the EU than the EU from the candidate country’s accession [15, p. 63], which allows the EU to impose conditions which the candidate has to meet.

The refugee crisis put the EU in a position where it depended on Turkey’s support to limit the flow of refugees to Europe. Unsurprisingly, in the course of negotiations for a refugee deal, Turkey acquired substantial leverage. The bargaining power that Turkey gained is exemplified by a widely quoted statement of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan from his meeting with the President of the Council Donald Tusk and the President of the Commission Jean-Claude Juncker: “We can open the doors to Greece and Bulgaria anytime and put the refugees on buses... So how will you deal with refugees if you don’t get a deal? Kill the refugees?” [16].

What could potentially prove to be even more damaging to conditionality beside Turkey’s leverage is that the two processes – accession negotiations and refugee negotiations – have not been kept apart.

To ensure Turkey’s help in counteracting the refugee flow, the EU promised in return to advance the accession negotiations and open additional negotiation chapters, which would normally be done as a “reward” for compliance with membership conditions. Turkey getting the rewards when it was not complying with the accession conditions undermined the main principle of conditionality, which is based on the idea that compliance with the conditions should be the only way to achieve the rewards.

The ultimate reward for compliance with the Copenhagen criteria is admitting the country to the Union. Beside the final reward, the accession process also includes intermediate rewards.

The biggest intermediate rewards are transitions to the next stage of the accession process whenever a country meets the necessary benchmark criteria. That translates into such important steps as receiving the candidate status and opening or closing the negotiations. When the accession negotiations are underway, the primary reward to mark and celebrate a country’s progress is opening and closing negotiating chapters2.

Two chapters – Ch. 17 (Economic and Monetary Policy), opened at the 11th EU-Turkey Accession Conference in December 2015, and Ch. 33 (Financial and budgetary provisions), opened at the 12th EUTurkey Accession Conference in June 2016, – were opened not for Turkey’s compliance with the criteria, but in exchange for Turkey’s help in curbing the flow of refugees to Europe.

The arrangements that came out of EU-Turkey refugee negotiations present an interesting case of the EU promising to advance the accession talks by, among other things, opening new chapters (a “reward” within the accession process) at the moment when the candidate country was not only failing to show progress, but was in fact backsliding.

The two frameworks – accession negotiations and a strategic partnership to combat the refugee crisis – intertwined, resulting in Turkey being rewarded with what was originally supposed to be a reward for progress on the path to becoming a democracy at the exact moment that Turkey was going in the opposite direction.

EU CONDITIONALITY BEYOND THE REFUGEE CRISIS

Although the EU’s dependence on Turkey during the refugee crisis could potentially explain a muted reaction to the gradual erosion of democracy and human rights beginning with 2015, the hesitancy in the EU’s reactions was evident even earlier than that.

The first Progress Report to explicitly mention significant backsliding on political criteria was released only in the autumn of 2015 [17]. The timing suggests that even in the light of the growing dependence of Europe on Turkey, the democratic backsliding and backsliding in the area of fundamental freedoms was reaching levels impossible for the EU to ignore.

Interestingly, the 2015 report specifies that the backward trend “was seen over the past two years” (which does coincide with data from democratic indices such as Freedom House and estimations in academic papers), there was no mention of such backsliding in either the 2013 or the 2014 reports. Additionally, even after the first official mention of “backsliding”, be it perhaps to some extent belatedly, no upgrade in counteracting measures followed: the ongoing refugee negotiations quite likely made the EU more hesitant to considerably change the rhetoric or take new measures.

That could explain why even after acknowledging and condemning democratic backsliding the EU continued to utilise largely the same measures as before.

However, the situation in Turkey continued to deteriorate, especially after a failed coup attempt in 2016. That prompted the EU to come up with new ideas on how to counteract authoritarian reversal. In November 2016, the European Parliament voted in favour of a resolution calling to suspend the accession negotiations [18].

The resolution being a non-binding call to the EU Commission (EC), the move came to be more of a symbolic nature. In the meanwhile, the already employed measures of reiterating the conditions and exposing and condemning Turkey’s non-compliance in the Progress Reports and public statements of EU leaders continued [19].

In 2017, the European Parliament again called on the EC and the Member States to initiate the procedure of suspending the negotiations should Turkey proceed with constitutional reforms changing the country into a presidential system with few checks and balances [20]. However, when Turkey failed to comply, no reaction followed from the Commission and the procedure of suspending the negotiations was not initiated. Even after the European Parliament voted for the third time to suspend accession negotiations in March 2019 [21], they remained officially ongoing.

The lack of reaction from the European Commission demonstrated the EU’s reluctance to resort to measures the EU itself included in the framework as a safeguard against democratic deterioration in candidate countries. Moreover, the situation exposed divergent preferences within the EU on how the consolidation of authoritarianism in Turkey should be handled.

That could potentially have negative consequences for the credibility of conditionality, which rests on the ability of the EU to act as a unified entity. That said, even failing to agree on whether negotiations have to be suspended, the EU managed to agree to recourse to another heavy measure available within the accession framework: cuts to pre-accession financial assistance [22].

This is the first time in EU enlargement history such a measure is evoked3. In the meanwhile, criticism in Regular Reports and in the statements from EU officials continued.

CONCLUSION: TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE?

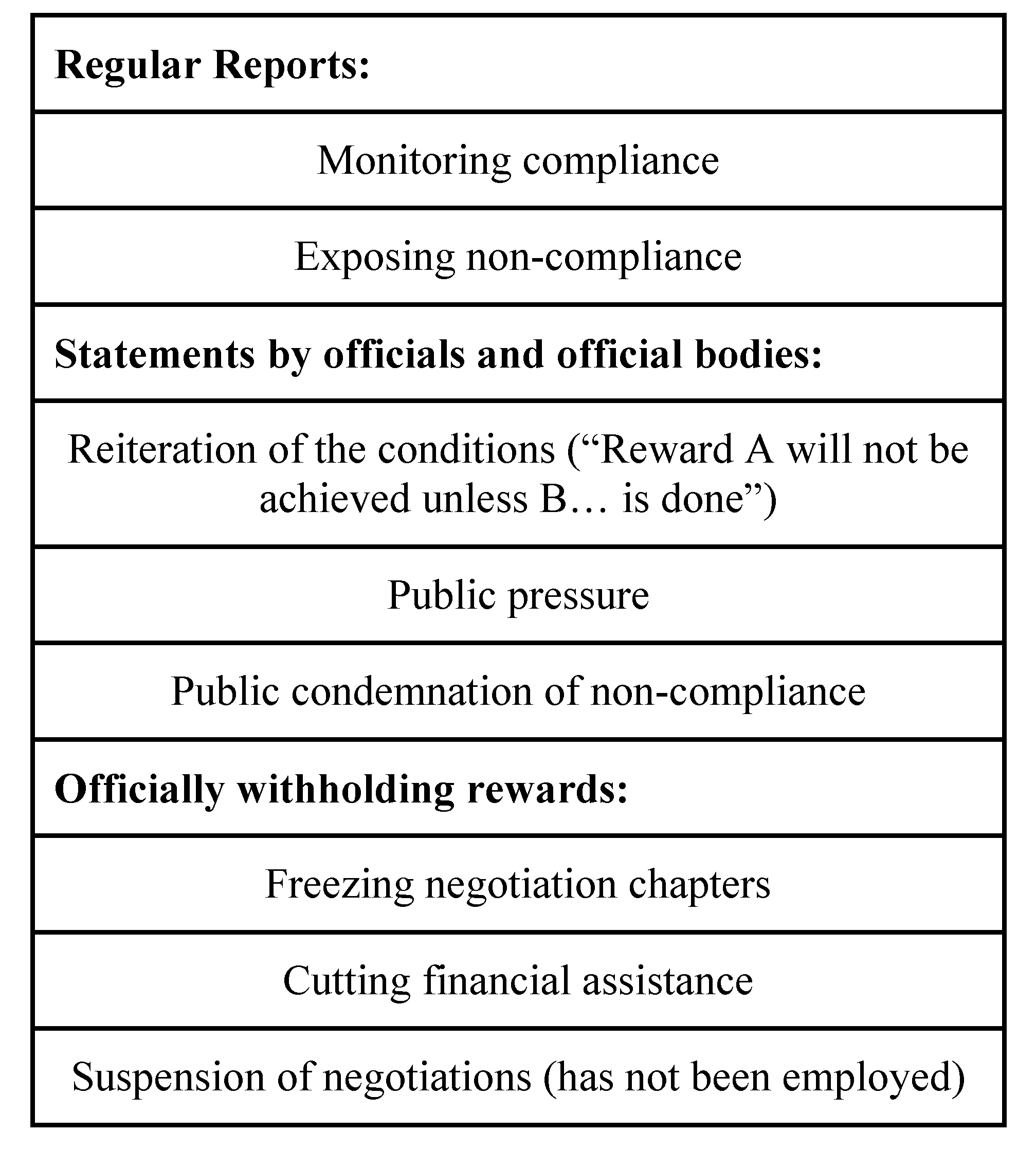

To sum up, one can notice the trend of “upgrading” the reactions to heavier ones as democratic deterioration in Turkey progressed. Starting with monitoring and exposing, moving to pressure and reiteration of the conditions and then to cutting financial assistance and openly discussing a possibility of suspending negotiations – the EU employed a range of possible tools, without having to step outside the bounds of positive conditionality (see Table). However, it remains questionable whether the measures employed by the EU were proportionately matched to the situation at the time they were employed.

Table

EU conditionality tools

Source: compiled by the author.

The two-year delay in officially exposing backsliding and the hesitancy to upgrade the countermeasures suggest that the responses were belated. The measures that could have worked at earlier stages of democratic backsliding failed to have much effect when autocratic reversal was in full force.

In fact, even though we have listed a number of measures that have or could have theoretically been employed by the EU, it is quite likely that the “take or leave it” approach of positive conditionality can prove to be powerless once a certain level of autocratic consolidation is achieved. If the regime is highly illiberal, that could indicate prohibitively high costs of compliance with EU criteria, rendering conditionality ineffective [23]. That said, it has to be noted that some of the problems the EU encountered are not related to the type of conditionality the EU employs. For example, both positive and negative conditionality rely on credibility, of either promises or threats.

The need to cooperate with Turkey to deal with the refugee crisis and the discrepancy between the Parliament’s and the Commission’s preferences would have had consequences for negative conditionality as well. As such, the lack of effectiveness may lie in the consistency of conditionality’s application no less than the type of conditionality.

Additionally, it should be pointed out that the EU previously had no expertise in dealing with severe backsliding in candidate countries. The need to enter an unfamiliar territory may explain some hesitancy to act and delays in the reactions. Belated reactions, combined with the need to stick to positive conditionality and the exogenous shock of the refugee crisis led to the lack of counteracting effect of EU conditionality against backsliding in Turkey.

References

Библиография

- 1. Vachudova M.A. EU Leverage and National Interests in the Balkans: The Puzzles of Enlargement Ten Years On. Journal of Common Market Studies. 2014. V. 52. № 1, pp. 122-138.

- 2. Muftuler-Bac M. Backsliding in judicial reforms: domestic political costs as limits to EU’s political conditionality in Turkey. Journal of Contemporary European Studies. 2019. V. 27. № 1, pp. 61-76.

- 3. Kmezic M. and Bieber F. The Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans: An Anatomy of Stabilitocracy and the Limits of EU Democracy Promotion. Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group Policy Paper. 2017.

- 4. Börzel T.A. Building Member States: How the EU Promotes Political Change in its New Members, Accession Candidates, and Eastern Neighbors. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations. 2016. V. 8. № 1, pp. 76-112.

- 5. Schimmelfennig F., Engert S. and Knobel H. Costs, Commitment and Compliance: The Impact of EU Democratic Conditionality on Latvia, Slovakia and Turkey. Journal of Common Market Studies. 2003. V. 41. № 3, pp. 495-518.

- 6. Gateva E. European Union Enlargement Conditionality. London, 2015.

- 7. Muftuler-Bac M. The Pandora's Box: democratisation and rule of law in Turkey. Asia-Europe Journal. 2016. V. 14, № 1, pp. 61-77.

- 8. European Commission. Turkey 2007 Progress Report. Brussels, 2007.

- 9. Saatçioğlu B. De-Europeanisation in Turkey: The Case of the Rule of Law. South European Society and Politics. 2016. V. 21, № 1, pp. 133-146.

- 10. European Commission. Turkey 2010 Progress Report. Brussels, 2010.

- 11. European Commission. Turkey 2013 Progress Report. Brussels, 2013.

- 12. Reuters. 21.01.2014.

- 13. Time. 06.02.2014.

- 14. European Commission. Turkey 2014 Progress Report, Brussels, 2014.

- 15. Vachudova M.A. EU enlargement and state capture in the Western Balkans. Dzankic, J., Keil, S. and Kmezic, M. (eds.). The Europeanisation Of The Western Balkans - A Failure of EU Conditionality? London, 2019, pp. 63-85.

- 16. Reuters. 8.02.2016.

- 17. European Commission. Turkey 2015 Progress Report. Brussels, 2015.

- 18. European Parliament. European Parliament resolution of 24 November 2016 on EU-Turkey relations, 2016/2993(RSP). Strasbourg, 2016.

- 19. Deutsche Welle. 25.07.2016.

- 20. European Parliament. European Parliament resolution of 6 July 2017 on the 2016 Commission Report on Turkey (2016/2308(INI)). Strasbourg, 2017.

- 21. European Parliament. European Parliament resolution of 13 March 2019 on the 2018 Commission Report on Turkey (2018/2150(INI). Strasbourg, 2019.

- 22. European Commission. Annex to the Commission Implementing Decision, C(2018) 5067 final. Brussels, 2018.

- 23. Schimmelfennig F. and Sedelmeier U. Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy. 2004. V. 11. № 4, pp. 661-679.