- PII

- S032150750026137-2-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032150750026137-2

- Publication type

- Article

- Status

- Published

- Authors

- Volume/ Edition

- Volume / Issue 6

- Pages

- 54-61

- Abstract

The Lake Chad (LC) region today is at crossroads, facing enormous security challenges from the Boko Haram / ISWAP insurgency with very important implications for regional stability. The largely unsecured borders of the region provide platforms for terrorist activities. Unarguably, cross-border security is a historical concern for the Lake Chad region countries.

The authors attempt to explore the emerging regionalisation of (in) security and externality of threats around the Lake Chad region. Using the framework of Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT), it conceptualises regional security within the trajectories of the threat in the region. RSCT provides a theoretical and conceptual framework for understanding the emergent structure and dynamics of regional security. The paper adopts the qualitative research method which offers an in-depth description and analysis of the regionalisation of security threats in the LC region.

The paper unveils that despite a plethora of research on resurging threats of violent terrorism and the huge publicity of Boko Haram activities in the Lake Chad region, little is known within academia on the element of ethno-cultural and historical tendencies in regional security in the LC region. It thus posits that addressing the challenge of regional security, especially in the Lake Chad would require holistic approach that takes into consideration the ethno-cultural and historical ties and challenges of the region.

- Keywords

- regional security, Regional Security Complex Theory, Lake Chad, MNJTF, terrorism

- Date of publication

- 21.06.2023

- Year of publication

- 2023

- Number of purchasers

- 15

- Views

- 719

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, regional security experts have been preoccupied with unveiling, among other things, the variables that foster regional (in)stability and (dis)order. This invariably reflects a confluence of the continuing relevance of traditional geostrategic calculations and the emergence of new security challenges that have redefined the content and scope of order in the contemporary international system. The rising salience of regional security and regional security orders which cut across every dimension of interaction has generated a surprisingly large number of formal regional arrangements that vary in scope, complexity, and strength [13; 25].

It is observed that the Lake Chad region (LCR) is currently at a crossroads. This is not unconnected with its lingering security challenges prominent among which is the Boko Haram insurgency that have had enormous security implication in the region [6]. The escalation of the activities of this extremist group around the LCR has resulted in litanies of carnages, blood bath and thousands of deaths in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria between 2011 and 2021. Such scenario creates what a British political scientist B.G.Buzan and a Danish professor of international relations O.Wæver [3] refer to as “regional security complex”; that is, the interconnectedness of complex security concerns among states that compels a form of collaboration or alliances. Researches over the years reveal that the largely unsecured borders in the Lake Chad region provide platforms for terrorist activities, especially Boko Haram [6].

This paper attempts to examine the spread of insecurity in the LCR. The analysis is embedded in a larger body of theoretical and empirical research on regional conflict formations. Substantial researches by F.C.Onuoha [23], T.S.Denisova [12], S.A.Bokeriya & D.O.Omo-Ogbebor [6], I.A.Bakare [2], etc. on Boko Haram radicalization, spread, insurgency and counterinsurgency continue to demonstrate the increase of regional manifestations of Boko Haram activities vis-a-vis increase in threat to regional security.

OVERVIEW OF THE SECURITY SITUATION IN THE LAKE CHAD REGION

The Boko Haram insurgency remained one of the major security threats to peace, stability and development in the Lake Chad Basin. The countries sharing common boundaries along the Lake Chad continue to grapple with security challenges resulting from the insurgency in the LCR, which comprises parts of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria [2].

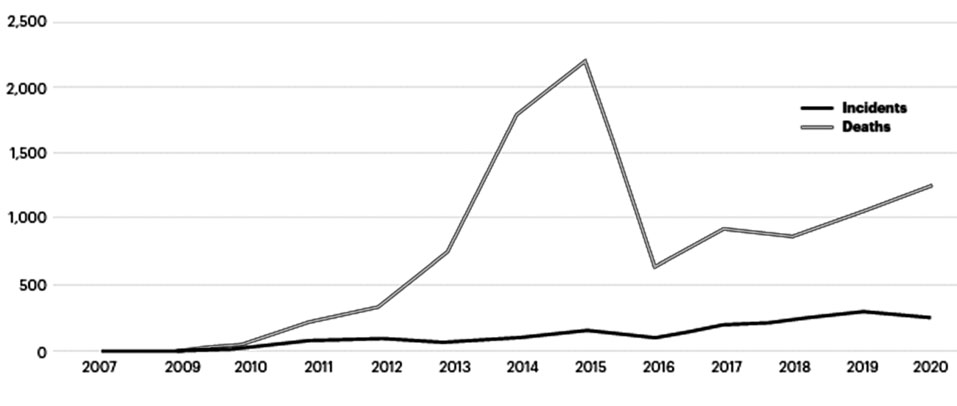

Conflict in this region is complicated by several ecological threats including water scarcity, high population growth, drought, desertification [18; 21], land degradation and food insecurity [15]. Within the region, approximately 90% of livelihoods rely on lake water and rainfall. However, this paper would be restricted to terrorist activities in the region. The current crisis in the LCR is often framed by the violence perpetrated by Boko Haram. Boko Haram and Islamic State – West Africa Province (ISWAP) have sought to exploit existing fragilities to perpetuate an unprecedented security crisis driven by persistent terrorist and violent extremist attacks, especially by Boko Haram. These attacks have resulted in thousands of deaths throughout the LCR. See Figure 1 for ease of reference, however a closer look at Figure 1 and 2 reveals a more complicated regional picture with the regional outlook of the threat and attacks of the group.

The spread of Boko Haram activities in the LCR of Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria has affected trade activities and businesses within the region. As of 2020, there were an estimated 2.7 mln Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the lake basin. The violence has also led to widespread of civilian displacement, disruption of agricultural production, livelihoods and restricted affected populations from accessing basic services [15].

Researchers have also argued that food security and rapid population growth in the LCR has contributed to the increase of Boko Haram which the latter has exploited over the years. For example, Global Terrorism Index in its 2022 report noted that the water situation around lake highlighted that not only are there around 30 mln people across Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon competing over dwindling water supplies but that Boko Haram looks to exploit this situation [15, p. 56]. The report further noted that food security has also contributed to the regionalisation of Boko Haram activities. The group, due to food insecurity, had had to go to Cameroon in search for food.

Figure 1. Total incidents and deaths from terrorism in the Lake Chad Basin, 2007–2020.

Source: [15].

There has however been improvement in terrorism deaths in the region which is attributed to the successful counter insurgency operations targeting Boko Haram where deaths caused by the group declined by 72% between 2020 and 2021 from 629 deaths to 178 deaths. In 2021, deaths in Nigeria fell by 51%, falling to 448 in 2021, the lowest level since 2011. Terror-related casualties dropped by almost half compared with the previous year. However, the number of terrorist attacks increased by 49% between 2020 and 2021. Though, this decline was attributed to a fall in deaths by Boko Haram and ISWAP and death of its leader Abubakar Shekau in May 2021. It is pertinent to note that the ISWAP overtook Boko Haram as the deadliest terror group in Nigeria in 2021 and, with an increased presence in neighbouring countries such as Cameroon and Niger, this continuous regionalisation of attacks and activities of the group present a substantial threat to the region [6; 15, pp. 2–4, 25].

Niger, on the other hand, for the first time is now amongst the ten countries most impacted by terrorism in 2021. Between 2020 and 2021 terror-related deaths almost doubled. In 2021, Niger recorded 588 deaths as a result of terrorism. Civilians accounted for 78% of these casualties, resulting in Niger becoming the country with the third-highest civilian death toll in 2021 [15, p. 27].

It is to be noted that Boko Haram unexpected resurgence after its founder was killed in 2009 was as a result of a mass prison break in September 2010. This was later accompanied by increasingly sophisticated and coordinated attacks in 2011 which progressed to include suicide bombings of police Headquarters building and the United Nations office in Abuja [14].

Consequent on the above, the recent coordinated attacks of the Kuje Custodial Centre (prison) in Abuja, Nigeria on 5th July, 2022, where terrorists were reported to have used high explosives and guns to breach the facility which led to the release and escape of over 800 of the 994 inmates and an Officer of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) and four inmates killed while 16 inmates were reported to have sustained various degrees of injuries during the attack, it would be anticipated that the consequential effect of 2010 prison break would be repeated. According to the spokesperson of the Nigeria Correctional Service, Umar Abubakar, on Wednesday 6th July, 2022, over 400 of the escaped inmates were recaptured while 443 were still at large. About 24 hours after the incident, ISWAP terrorist group claimed responsibility for the attack [22].

The continuous rise of Boko Haram / ISWAP and attacks on police stations and military establishment, Correctional facilities, churches and other places of worship, schools, international agencies, market squares and other highly-public targets has increased heightened tension, anxiety and a sense of insecurity and gross instability hitherto unknown in any part of the Lake Chad region.

REGIONAL SECURITY AND REGIONAL SECURITY COMPLEX: THE LAKE CHAD REGION IN PERSPECTIVE

To understand regional security, this section will adopt Barry Buzan’s Regional Security Complex Theory (RSCT) that was first introduced in the first edition of the book titled “People, States and Fear” in 1983. Updates to the theory were presented in Buzan (1991) [8], while a revised version of RSCT was introduced by B.Buzan, O.Wæver and J. de Wilde in 1998 [9] and Buzan and Wæver in 2003 [4]. This section therefore emphasizes the role of the LCR as central to the RSCT, where nations are close to the point where their security elements cannot be considered separate from each other [3]. As a term, “Lake Chad”, albeit still contested in its meaning, did not gain much currency until after the outbreak of Boko Haram terrorist group, especially during the spillover of attacks in Cameroon, Chad and Niger [26]. Here, we use the neologism Lake Chad as referring to the geographical area situated at the junction of West Africa and Central Africa, on the one hand, and Sahel, on the other hand.

A security complex is defined as ‘a group of states whose primary security concerns link together closely enough that their national securities cannot realistically be considered apart from one another’ [8], that is States affected by one or more security externalities that emerge from a different geographic area, as a result of geographical proximity. The countries of the Lake Chad region exemplify a region characterized by violent extremism that results from one country and impacts on another [28].

Thus an American political analyst Robert E.Kelly, the author of “Security Theory in the ‘New Regionalism’” [19] submits that regional subsystems are porous, proximity qualifies the security dilemma dramatically, and weak state-dominant regional complexes generate a shared internal security dilemma that trumps the external one. When examining the intersecting national boundaries in the LCR, it is helpful to visualise a braid. Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria each potentially represent a ‘thread’ that is defined not only by its borders, but more so by multiple ethnic groups, languages, traditions and beliefs. Such elements are further (inter)woven into a vast and diverse topography that ranges from dense forest and savannah from one end to another. An examination of this region reveals deceptively clear state boundaries that are challenged by the reality of porous borders, which allow goods and people to travel between states, contributing to the patchwork nature of this region. Such fluidity has much significance as problems and events often reverberate across state boundaries [16]. Security complexes are also generated by the interaction of anarchy and geography in the sense that anarchy confronts all states with the power-security dilemma, while security interdependence is powerfully mediated by the effects of geography. This is because threats operate more potently over short distances, security interactions with states in close proximity tend to have first priority.

On 26 August 2011, Boko Haram conducted its first high-profile international target – an attack against a Western interest in Abuja, Nigeria when a suicide bomber crashed a car into the United Nations building and detonated an explosive, which killed at least 23 people and injured more than 80 others. At the beginning it seemed to be a strictly Nigerian affair. Since 2014 the threat and attacks of Boko Haram took a regional dimension. The attacks on civilians and military positions in northern Cameroon witnessed its increase since March 2014, similarly southern Niger and western Chad had since early February 2015 witnessed increase in attacks from the Boko Haram.

Cross-border security is a historical concern for the Lake Chad region countries. The development of Boko Haram / ISWAP as a transnational threat in the Lake Chad region of Africa is attributed to several factors. The main factor was the favourable geographic terrain. For example, the specific type of dense forest terrain allowed the Boko Haram / ISWAP ease of movement in and between the affected countries. This is also linked to the porous borders of the countries in these parts of the Lake Chad region which unarguable contributed to the mobility of the terrorist groups leading to regional security issue. The transnational element not only refers to the movement of the Boko Haram / ISWAP but also to its economic sustenance through cross-border kidnapping and movement of weapons. Consequently, the audacity of Boko Haram / ISWAP grew with the proliferation of weapons in the Sahara-Sahel region [24; 27].

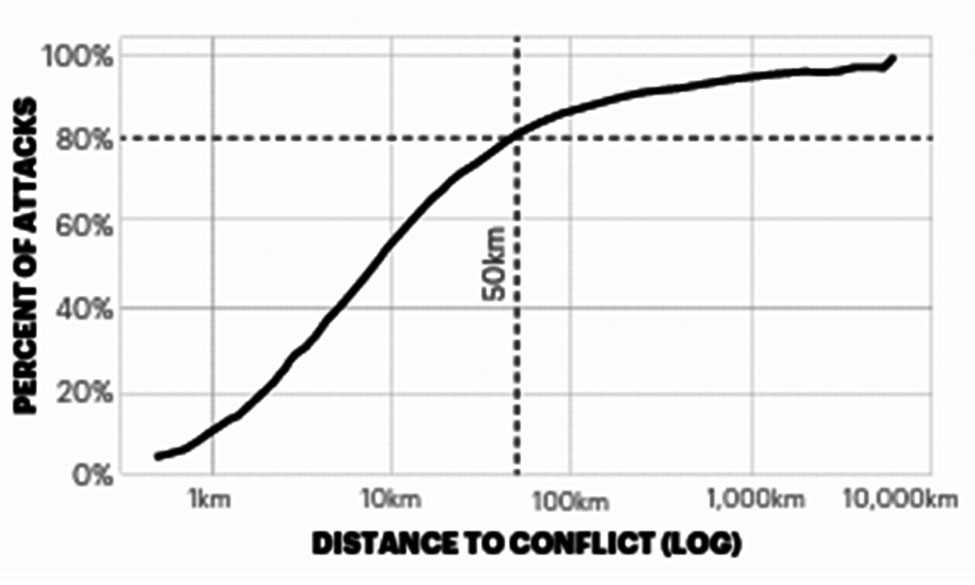

Unarguably, proximity plays a huge factor in regional (in)stability, between the countries that share borders. Instability could be exported from one country to another when insurgents establish strongholds in the border zones. Insurgents carry out attacks on neighbouring countries from the base camps [26]. Supporting this assertion is the submission by Global Terrorism Index-2022 [15], according to its report, geographically (as shown in Figure 2) 80% of all terrorist attacks occur within 50 km of a conflict. This has helped analysts to argue that the (in)stability of the border reflects the level of violence or cooperation experienced. When borders are fortified and militarized owing to the threat of violence and instability experienced, violent attacks at the local level are certainly impeded by such cooperation [20]. Thus, the regional proximity factor has acquired great importance as a tool to analyze the international relations, regional relation / security dynamics and the innovative national approach to the international opening [7].

Figure 2. Proximity of Terrorist Attacks from Armed Conflict.

Source: [15].

The idea of security complexes is an empirical phenomenon with historical and geopolitical roots. Specifically, ethno-cultural thinking, as well as religious and racial ties underlie much traditional historical analysis. Such ties constitute a significant factor in identifying security complexes since shared cultural characteristics among a group of states would cause them both to pay more attention to each other [5]. For instance, the LCR is the meeting place of various populations. People living within Lake Chad, whether Cameroonians, Chadians, Nigériens or Nigerians fed on the resources from the Lake Chad, including its waters, fishing, agriculture and livestock.

Similarly, Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri, etc. are major ethnic groups of the LCR. The Kanuri people are an ethnic group living largely in Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, etc. Kanuri groups have traditionally been sedentary, engaging in farming, fishing, trade and salt processing. The home territories of the Hausa people lie on the border between Niger and Nigeria [17]. Evidently, borders are institutions that regulate the interface between political communities. Unarguably, this cross-border link of ethnic groups and the predominant pastoralism has the potentials of fueling violence and insecurity across the region by extension associating ethnic groups, historical and geopolitical roots and ethno-cultural thinking with the expansion of threats. Threats/violence at the borderline would possibly lead to regional instability, as such threat/instability could be exported from one country to another, especially when insurgents establish strongholds in the border zone. This could lead to possible regional security concern and eventually regional security formation between the countries affected, in order to counter the threats.

REGIONAL SECURITY FORMATION/ REGIONAL SECURITY ARCHITECTURE: MNJTF AS A CASE STUDY

B.Buzan and O.Wæver as espoused, a regional security complex is a group of states whose primary national security concerns are so closely intertwined together that they cannot be extracted or addressed independently of each other, hence, the existence of an element of relationships and dependencies. The theory views security interdependence as a critical factor in the creation of regionally based clusters. RSCT provides a framework for analysis of regional security of regions. To this end, this section explores Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) as the emerging regional security architecture in the LCR to fight terrorism and insurgency. It diagnoses the evolution of the MNJTF as a sub-regional security architecture that unites the fight against a common threat between Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria. Military strategies are crucial tools for the protection of the strategic interests of participating countries in regional military alliance. The choices of States to participate in regional military alliances or collaboration are inextricable link with the States’ strategic national interest [4].

The history of MNJTF begins in 1994. Due to the emergence of security threats such as smuggling in the Lake Chad in the 1990s, at the 8th Summit of the Lake Chad Basin Commission held in Abuja in 21–23 March 1994, heads of state of member-countries decided to establish a joint security force based in Baga-Kawa in Nigeria to contain and checkmate criminal activities and to facilitate free movement in the vast ungoverned areas of the region in the shared border areas. Its main mission was to curb arms smuggling around the border of the Lake Chad [11]. Nigeria, during the administration of Sani Abacha, was however the only country that contributed troops. The force was later expanded in 1998 to include units from neighbouring Chad and Niger with the purpose of dealing with common cross-border security issues in the LCR which led to the creation of the MNJSF [1].

The proliferation and intensification of Boko Haram’s terrorist attacks in Nigeria and in parallel Ansaru’s attacks (a branch that split from Boko Haram due to ideological differences), the deterioration of the security situation in the Lake Chad region, its humanitarian, security and developmental consequences, compelled decision-makers in Nigeria, Chad and Niger to change the force’s designation from dealing with common cross-border security issues in the LCR and expand it. In April 2012, the mandate of the MNJTF was expanded to include anti-subversive combat (counterinsurgency). Following the necessary adjustments, the coalition force was activated from July 30, 2015 as a combined military force against Boko Haram with the participation of military forces from Cameroon, Chad, Niger, Benin and Nigeria [11].

The Baga’s attack in January, 2015 marks the turning point in the regional fight against Boko Haram. Boko Haram fighters surprised and attacked with considerable force the town of Baga (about 10,000 inhabitants), which serves as a commercial junction, a fishing market and the MNJTF headquarters. Killing local population and numbers of Nigerian soldiers, including demolishing and burning 620 buildings, which includes the multinational force headquarters. For over a decade, violent extremism has spread across the region as a result of Boko Haram and ISWAP activities. This has given the impulse to regional security cooperation processes – a joint military force mandated by the African Union Peace and Security Council (PSC), with the support of external partners [29; 10].

From the beginning of 2020, the joint force amount to about 10,000 fighters with its current commander Maj Gen J.J.Ogunlade. The headquarters is in Ndjamena, Chad. To ease operations, the combat zone in the region was divided into the following 4 sectors and each member state was given responsibility for each sector: Sector 1 (Cameroon) headquartered at Mora; Sector 2 (Chad) headquartered at Baga-Sola; Sector 3 (Nigeria) based in Baga; and Sector 4 (Niger) based in the town of Diffa [11].

From 2015, the several large-scale transnational operations that have been carried out by the MNJTF to limit and halt military capabilities and operations of the terrorist groups have obtained diverse degrees of success. However, element of internal security challenges in the Eastern part of Nigeria and Chad as well as Southern part of Cameroon which has led to the deployment of troops to these affected areas would inadvertently constrain and contribute to scaling back the effectiveness and success of the MNJTF. To this end, the competition between national interests and regional cooperation rationales could be major factors of weakness [10].

Unarguably, regional organizations/architectures serve to repress shared centrifugal threats through pooled rather than ceded sovereignty, hence the MNJTF. The nexus between national and regional security, with an emphasis on politico-military cooperation to tackle terrorism, underpins the emerging concept of regional security/architecture. It is defined and as examined above, is “a set of units whose major threats are so interlinked that their security problems cannot reasonably be analysed or resolved apart from one another”.

CONCLUSION

The Lake Chad region is fast emerging as a new security complex. In addition to the LCR shared resources, countries of the region demonstrate a number of factors in common, least is the geographical proximity, political problems, socio-ethno-cultural linkages, religious and social ties, economic resources and shared threats to national and regional security. The countries of the Lake Chad region exemplify a region characterized by violent extremism that results from one country and impacts on another. This supports the claim that the idea of security complexes is an empirical phenomenon with historical and geopolitical roots.

This thread of ethno-cultural and historical ties within the borders that are challenged by the reality of porosity are elements that could be trajectories of conflict and it would cause the states to pay more attention to each other in forming regional security cooperation/alliance aimed at addressing its common regional threats. The analysis of these trends helps anticipate how regional security will affect a region. If ignored the vacuum of such trend would create lack of a standard regional methodology for addressing the menace and in turn makes it harder to contend with.

Therefore, this paper contributes not only to understanding common conceptions on security concerns between members of a given region with a common regional security dynamics of increased threat. It thus posits that addressing the challenge of regional security, especially in the LCR would require holistic approach that takes into consideration the ethno-cultural and historical ties and challenges of the region. Consequently, policies with local ownership and consideration would balance the expediency of regional security. Hence, the kinetic militaristic strategies of regional clusters alone cannot combat violent extremism and defeat terrorism unless strategies are conducted in tandem with historical and ethno-cultural tendencies while addressing the root causes such as marginalization, poverty and social exclusion, injustice, lack of rule of law, and bad governance, including considering creating conducive economic atmosphere.

References

- 1. Amandine Gnanguênon. Maping African Regional Cooperation: Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC). European Council of Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/special/african-cooperation/lcbc/ (accessed 20.07.2022)

- 2. Bakare I.A. International efforts in fighting Boko Haram: United Nations and African Union as case study. Аsia and Africa today. 2017. № 5. Pp. 17–20.

- 3. Barney Walsh. 2020. Revisiting Regional Security Complex Theory in Africa: Museveni’s Uganda and Regional Security in East Africa, African Security, 13:4, 300–324. DOI: 10.1080/19392206.2021.1873507

- 4. Barry Buzan & Ole Waever. 2003. Regions and Powers: the structure of international security. New York, United States: Cambridge University Press.

- 5. Bettina Koch and Yannis A.Stivachtis. Introducing Regional Security in the Middle East. E-International Relations. May 11, 2019. https://www.e-ir.info/2019/05/11/introducing-regional-security-in-the-middle-east/; https://www.e-ir. info/pdf/78703 (accessed 20.07.2022)

- 6. Bokeriya S.A., Omo-Ogbebor O.D. Boko Haram: a new paradigm to West Africa security challenges. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations. 2016. Vol. 16. № 2. Pp. 274–284. Moscow.

- 7. Bordignon Marta & Cianci, Matilde & Lenzi, Francesca Romana. 2010. Regional Proximity Factor: An Advantage or a Disadvantage for Development? Transition Studies Review. 17. 356–373. DOI: 10.1007/s11300-010-0147-1

- 8. Buzan Barry. 1991. People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era. 2nd edition, London: Harvester Wheatscheaf.

- 9. Buzan B., O. Waever and J. De Wilde. Security: A New Framework of Analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998.

- 10. Camillo Casola. Multinational Joint Task Force: Security Cooperation in the Lake Chad Basin. ISPI. 19 March, 2020. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/multinational-joint-task-force-security-cooperation-lake-chad-basin-25448 (accessed 30.06.2022)

- 11. David Doukhan. 2020. Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram – Reflections. International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT). (accessed 30.06.2022)

- 12. Denisova T.S. Nigeria: from Maitatsine to Boko Haram. Vostok/Oriens. 2014. № 4. Pp. 70–82. Moscow. (In Russ.)

- 13. Fawn Rick. Regions’ and Their Study: Wherefrom, What for and Whereto? Review of International Studies, 2009. Vol. 35, pp. 5–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20542776 (accessed 01.07.2022)

- 14. Idahosa S.O. & Chukujekwu E.F. Domino theory for the promulgation of instability in the Sahel region: post Gadhafi era in perspective. Revista Inclusiones, Vol: 7 num Especial (2020): 240–250. P. 244.

- 15. Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, March 2022. http://visionofhumanity.org/resources (accessed 27.06.2022)

- 16. Jennifer Giroux, David Lanz, Damiano Sguaitamatti. The Tormented Triangle: The Regionalisation of Conflict in Sudan, Chad and the Central African Republic. Crisis States Research Centre: Working Paper № 47, Series 2. April 2009.

- 17. John Ogunsemore. Full List: Hausa is World’s 11th Most Spoken Language. https://www.herald.ng/full-list-hausa/ (accessed 30.08.2022)

- 18. Kateřina Rudincová. Desiccation of Lake Chad as a cause of security instability in the Sahel region. GeoScape. 2017, 11(2). 112–120. DOI: 10.1515/geosc-2017-0009

- 19. Kelly Robert E. Security Theory in the ‘New Regionalism’ (May 1, 2007). International Studies Review, 2007, 9/2, 197–229. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2384769 (accessed 30.08.2022)

- 20. Kenneth A. Schultz. Borders, Conflict, and Trade. Annual Review of Political Science. 2015. 18: 125–45.

- 21. Middendorp Tom, and Reinier Bergema. The Warning Signs are Flashing Red. The interplay between climate change and violent extremism in the Western Sahel. The Hague: ICCT, September 2019. https://icct.nl/app/uploads/ 2019/10/PB-The-Warning-Signs-are-flashing-red_2e-proef.pdf (accessed 30.08.2022)

- 22. Nasir Ayitogo. Abuja Prison Attack: Nigerian govt releases details of escaped Boko Haram terrorists. Premium Times. July 8, 2022. https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/541571-just-in-abuja-prison-attack-nigerian-govt-releases-details-of-escaped-boko-haram-terrorists.htm (accessed 30.07.2022)

- 23. Onuoha Freedom C. The audacity of the Boko Haram: Background, analysis and emerging trend. Security Journal. 25.2 (2012): 134–151.

- 24. Prosper Addo. Cross-border Border Criminal Activities in West Africa: Options for Effective Response. KAIPTC Paper № 12. May, 2006. http://iffoadatabase.trustafrica.org/iff/cross-border_criminal_activities_in_west_africa_options_for_effective_responses.pdf (accessed 29.09.2022)

- 25. Robert Stewart-Ingersoll, Derrick Frazier. 2013. Regional Powers and Security Orders: A Theoretical Framework. Routledge. ISBN 9780415631785

- 26. Stephen Osaherumwen Idahosa & Ilesanmi Abiodun Bakare. 2022. Conceptualisation of regional instability in Sahel: modelling ABM–AfriLand-Rebel Approach, Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 40:2, 190–205, DOI: 10.1080/ 02589001.2020.1796946

- 27. Tafotie D.J.R., Idahosa S.O. 2016. Conflicts in Africa and Major Powers: Proxy Wars, Zones of Influence or Provocating Instability. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations, 16 (3), pp. 451–460.

- 28. Usman A. Tar and Mala Mustapha. The Emerging Architecture of a Regional Security Complex in the Lake Chad Basin. Africa Development, Vol. XLII, № 3, 2017, pp. 99–118.

- 29. William Assanvo, Jeannine Ella A Abatan and Wendyam Aristide Sawadogo. West Africa Report: Assessing the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram. Institute for Security Studies. Issue 19, September 2016. https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/war19.pdf (accessed 30.07.2022)